Did Edison Accidentally Make Graphene in 1879?

In the annals of scientific history, serendipitous discoveries have often paved the way for groundbreaking innovations. Now, a team of researchers suggests that one of the most celebrated inventors of the 19th century, Thomas Edison, may have inadvertently created graphene over a century before it was formally identified and celebrated as a Nobel Prize-winning achievement.

Graphene, the thinnest material known to man, is a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. This unique structure gives graphene remarkable properties, from exceptional electrical conductivity to remarkable tensile strength. In recent years, graphene has emerged as a key material with countless applications, from high-performance batteries and supercapacitors to water filters and touchscreen displays.

The discovery of graphene in 2004 by Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov earned them the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics, marking a major milestone in the field of materials science. However, the new research published in the journal ACS Nano posits that the origins of graphene may trace back to Edison's pioneering work on incandescent light bulbs in the late 1800s.

"To reproduce what Thomas Edison did, with the tools and knowledge we have now, is very exciting," said James Tour, a chemist at Rice University and co-author of the study. "Finding that he could have produced graphene inspires curiosity about what other information lies buried in historical experiments. What questions would our scientific forefathers ask if they could join us in the lab today? What questions can we answer when we revisit their work through a modern lens?"

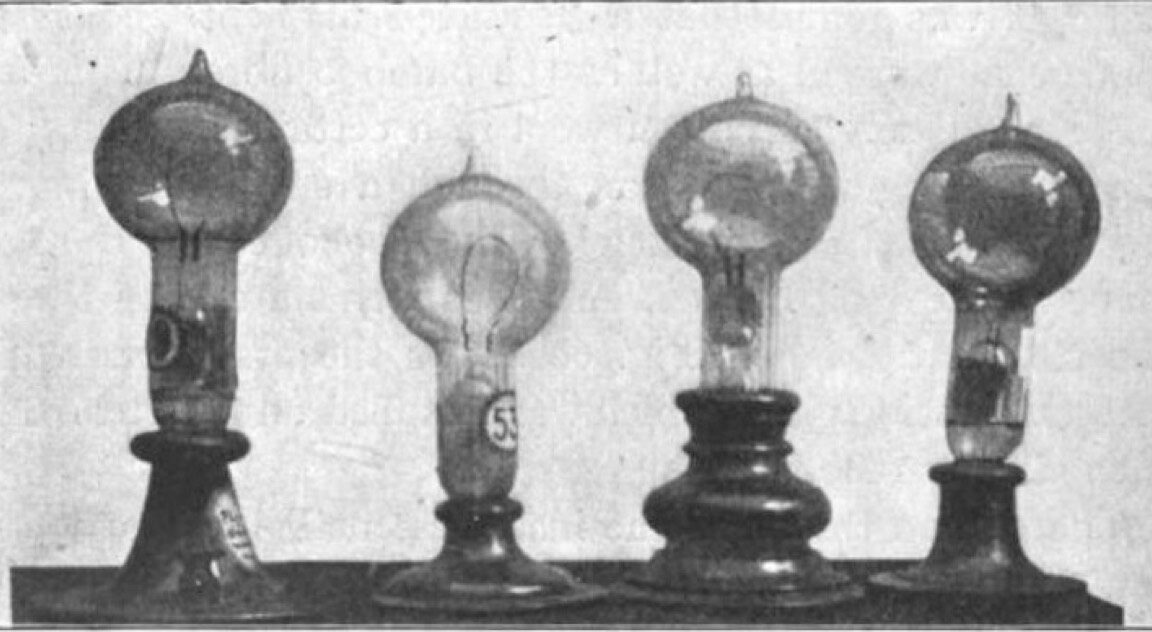

The story begins with Edison's relentless pursuit of the perfect filament material for his incandescent lamps. While the concept of incandescent lighting was not new, earlier designs had significant limitations, including short lifespans and high power consumption. Edison set out to overcome these challenges, experimenting with a wide range of materials to find the ideal filament.

After trying various carbonized materials, including cardboard, lampblack, and even different types of grasses and canes, Edison eventually discovered that carbonized bamboo made for the best filament. These bamboo-based filaments could last over 1,200 hours, a significant improvement over earlier designs, using a 110-volt power source.

It was during these experiments that the researchers believe Edison may have inadvertently created graphene. The process of carbonizing the bamboo, which involves heating the material in the absence of oxygen, could have resulted in the formation of graphene sheets as a byproduct.

"Finding that he could have produced graphene inspires curiosity about what other information lies buried in historical experiments."

To support this hypothesis, the researchers reproduced Edison's experiments using modern analytical techniques, including scanning electron microscopy and Raman spectroscopy. Their analysis revealed the presence of atomically thin carbon structures that closely resemble the characteristics of graphene.

"The structural features we see are identical to what we see in modern graphene, just produced in a more archaic fashion," Tour explained. "We're talking about single-atom-thick sheets of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal pattern."

While Edison's primary focus was on developing a reliable, long-lasting filament for his incandescent lamps, the potential byproduct of graphene could have far-reaching implications. The researchers suggest that if Edison had been aware of the unique properties of graphene, he may have been able to unlock even more of its potential, potentially accelerating the development of this revolutionary material by over a century.

"What questions would our scientific forefathers ask if they could join us in the lab today?" Tour mused. "Imagine if Edison could see the applications of graphene that we have today. He might have pivoted his research efforts to explore the material's potential, rather than solely focusing on improving the incandescent light bulb."

The implications of this discovery go beyond just the historical significance. By revisiting the work of pioneering scientists like Edison through a modern lens, researchers can gain valuable insights and inspire new lines of inquiry. This process of "historical reverse engineering," as Tour describes it, could uncover hidden gems in the annals of science, leading to unexpected breakthroughs and innovations.

"When we look back at the work of our scientific forefathers, we often assume that they were limited by the tools and knowledge available at the time," said Tour. "But the reality is that they may have stumbled upon important discoveries that were overlooked or misunderstood. By reexamining their work with modern techniques and perspectives, we can unlock new avenues of exploration and potentially accelerate the pace of scientific progress."

The discovery of Edison's potential role in the history of graphene serves as a powerful reminder of the serendipitous nature of scientific advancement. It also highlights the importance of maintaining a curious and open-minded approach to the past, as the answers to some of today's most pressing challenges may be hiding in plain sight, waiting to be rediscovered and reinterpreted for the modern era.

As the world continues to unlock the incredible potential of graphene, the story of its possible origins in Edison's incandescent lamp experiments serves as a captivating chapter in the ongoing saga of scientific discovery. It is a testament to the power of curiosity, persistence, and the willingness to challenge established narratives, traits that have defined the greatest scientific achievements throughout history.